A skip list is an ordered data structure based on a linked list that allows for fast lookups and insertions. The time complexity for insertion, lookup, and deletion is O(log N), and it remains sorted after these operations. Redis’s SortedSet data type is implemented using a skip list.

The skip list is an elegant data structure that perfectly embodies the “space-for-time” trade-off. Let’s consider the problem with a traditional sorted linked list:

HEAD -> (-10) -> (1) -> (2) -> (3) -> (10) -> TAIL

If we want to insert a node with a key of 5, we need to place it between 3 and 10. However, the complexity of this insertion is O(N) because we have to traverse the list to find the correct position. The same applies to search and delete operations.

The reason for this is that traversal can only happen one node at a time, as each node has only a single next pointer. A skip list, as the name suggests, allows for “skipping” during traversal. A node in a skip list has multiple levels of pointers, stored in a forward array. Pointers at higher levels jump farther, while the pointer at the lowest level always points to the immediate next node.

This might be hard to grasp from the definition alone, but the structure of a skip list becomes clear with a diagram:

L3 |HEAD -> (-10: -10)---------- -> (2: 2)---------------------- -> TAIL

|(1) (2) (3)

|| | | |

L2 |HEAD -> (-10: -10) -> (1: 1) -> (2: 2)---------------------- -> TAIL

|(1) (1) (1) (3)

|| | | | |

L1 |HEAD -> (-10: -10) -> (1: 1) -> (2: 2)---------- -> (10: 10) -> TAIL

|(1) (1) (1) (2) (1)

|| | | | | |

L0 |HEAD -> (-10: -10) -> (1: 1) -> (2: 2) -> (3: 3) -> (10: 10) -> TAIL

|(1) (1) (1) (1) (1) (1)

Here, (-10: -10) represents the key and value. The (2) below it indicates that the pointer at this level jumps to the 2nd node after it, meaning it skips 1 node in between.

Although a skip list is drawn like a matrix, it is still fundamentally a linear linked list. In reality, the entire skip list consists of n actual nodes plus two optional sentinel nodes (head, tail). The difference is that each node has multiple pointers instead of just one. Higher-level pointers jump farther, and lower-level pointers make shorter jumps.

All traversals in a skip list start from the top-left corner, which is the head node at the highest level (self.level). The process involves moving right and then moving down. Let’s take searching for 10 as an example:

- Start at the

headnode, at level 3. - Jump right to the

-10node. - Jump right to the

2node. - The next node at this level is the

tail, so move down to level 2. - The next node at level 2 is also the

tail, so move down to level 1. - The next node is

10. The search is complete.

Moving down a level has almost no performance cost (it’s just a calculation like current_level -= 1), so we can ignore it for now. The search operation above visited 3 nodes (excluding the head) to find the node 10. If we were to traverse from level 0 (the basic linked list), it would require 5 visits. Therefore, the search performance of a skip list is better than that of a linked list.

Unlike strictly balanced ordered structures like AVL or Red-Black trees, the balance of a skip list is probabilistic because the level of each node is generated randomly. Ideally, there should be fewer nodes at higher levels, allowing for longer jumps and skipping more nodes.

The simplest way to generate the level for a new node is generally:

fn random_level() -> i32 {

let mut level = 0;

while rand::random::<f64>() < 0.5 && level < MAX_LEVEL {

level += 1;

}

level

}

This means a node’s level has a 50% chance of increasing by 1 on each coin flip, up to a maximum height. So, the probability of level = 1 is 50%, level = 2 is 25%, level = 3 is 12.5%, level = 4 is 6.25%, and so on.

The value of MAX_LEVEL is an attribute of the skip list itself, typically 16 or 32. It represents the maximum possible height, not the maximum number of elements. Even if the maximum height is reached, you can still insert elements indefinitely, but the performance optimization becomes less significant.

Due to this randomness, the structure of a skip list is not deterministic. For the exact same sequence of insertions, the resulting skip list structures will very likely be different. Despite the randomness, with our rand_level method, the expected number of nodes at any level is half that of the level below it. This means that moving down a level eliminates about half of the remaining nodes, similar to a binary search tree. Therefore, the average time complexity is O(log N).

The skip list described so far has a problem: it cannot quickly access the nth element. You still have to traverse from level 0, the linked list structure. However, this is easy to solve. We can add a span value to each pointer in the forward array, indicating the number of nodes the pointer skips over (including the target node). This way, we can accumulate the total number of nodes skipped during traversal. When the total equals n, we’ve found our element. If a jump would overshoot the target, we move down a level. Since the span of every pointer at level 0 is always 1, we are guaranteed to find the nth element as long as n is less than the total number of nodes.

pub trait Key: Ord {} // Key must implement Ord

impl<T> Key for T where T: Ord {}

pub trait Value {}

impl<T> Value for T {}

pub struct Node<K, V> {

key: MaybeUninit<K>,

value: MaybeUninit<V>,

forward: Vec<ForwardPtr<K, V>>,

level: usize,

}

impl<K: Key, V: Value> Node<K, V> {

pub fn key(&self) -> &K {

unsafe { self.key.assume_init_ref() }

}

pub fn key_mut(&mut self) -> &mut K {

unsafe { self.key.assume_init_mut() }

}

pub fn value(&self) -> &V {

unsafe { self.value.assume_init_ref() }

}

pub fn value_mut(&mut self) -> &mut V {

unsafe { self.value.assume_init_mut() }

}

}

type NodePtr<K, V> = NonNull<Node<K, V>>;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct ForwardPtr<K, V> {

ptr: NodePtr<K, V>,

span: usize, // forward_ptr carries span information

}

// We must manually implement Clone here, we can't use derive

// because #[derive(Clone)] would generate code like:

//

// impl Clone for ForwardPtr

//

// which requires K and V to implement Clone, but we cannot restrict K and V to be Clone.

impl<K, V> Clone for ForwardPtr<K, V> {

fn clone(&self) -> Self {

Self {

ptr: self.ptr,

span: self.span,

}

}

}

impl<K, V> Copy for ForwardPtr<K, V> {}

impl<K, V> PartialEq for ForwardPtr<K, V> {

fn eq(&self, other: &Self) -> bool {

self.ptr == other.ptr

}

}

impl<K, V> Default for ForwardPtr<K, V> {

fn default() -> Self {

Self {

ptr: NonNull::dangling(),

span: 0,

}

}

}

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct SkipList<K: Key, V: Value> {

head: NodePtr<K, V>,

tail: NodePtr<K, V>,

level: usize, // The level of the skip list is equal to the level of the highest node

len: usize,

}

const MAX_LEVEL: usize = 32;

Similar to the Red-Black Tree, since the key and value of the sentinel nodes head and tail cannot hold values, we need to use MaybeUninit. Unlike the Red-Black Tree, the IntoIter for a skip list can release nodes after each iteration because it doesn’t need to preserve the tree structure to find the successor. Therefore, we don’t need to use ManuallyDrop for the key and value.

The insertion/deletion logic for a skip list is much simpler than for a Red-Black Tree. The core idea is to traverse from the highest level down, maintaining an update array. After traversing level i, the current node pointer is stored in update[i]. Once the initial traversal is complete, we iterate through the update array from the highest level down. For an insertion, we insert the new node at level i after the node pointed to by update[i].

pub fn insert(&mut self, key: K, value: V) -> Option<V> {

let level = Self::rand_level(); // Generate a random level

// If the new level is greater than the skip list's current level, update the list's level

// and make the new level pointers in the head point to the tail.

if level > self.level {

for _ in (self.level + 1)..=level {

unsafe {

self.head.as_mut().forward.push(ForwardPtr {

ptr: self.tail,

span: self.len + 1,

});

}

}

self.level = level;

}

// update[i] stores the pointer to the node at level i that needs to be updated.

// It points to the last node at level i with a key less than the new key.

let mut update = vec![NodePtr::dangling(); self.level + 1];

let mut steps = vec![0; self.level + 1];

let mut step = 0;

let mut cur = self.head;

for i in (0..=self.level).rev() {

loop {

let cur_node_ref = unsafe { cur.as_ref() };

let next = cur_node_ref.forward[i].ptr;

if self.is_tail(next) {

break;

}

let next_key = (unsafe { next.as_ref() }).key();

// If the node's key is less than the current key, continue.

if next_key < &key {

step += cur_node_ref.forward[i].span;

cur = next;

} else {

break;

}

}

update[i] = cur;

steps[i] = step;

}

let mut next = unsafe { cur.as_ref() }.forward[0].ptr;

if !self.is_tail(next) && unsafe { next.as_ref() }.key() == &key {

// If the key already exists, update the value and return the old value.

let old_v = std::mem::replace(unsafe { next.as_mut() }.value_mut(), value);

return Some(old_v);

}

cur = next;

step += 1;

let mut forward = vec![ForwardPtr::default(); level + 1];

let new_node = Box::new(Node {

key: MaybeUninit::new(key),

value: MaybeUninit::new(value),

forward: vec![],

level,

});

let mut new_node_ptr = NonNull::from(Box::leak(new_node));

// Update each update[i]

// new_node.forward[i] = update[i].forward[i]

// update[i].forward[i] = new_node

for i in (0..=self.level).rev() {

let update_node = unsafe { update[i].as_mut() };

if i <= level {

let cur_span = step - steps[i];

forward[i] = ForwardPtr {

ptr: update_node.forward[i].ptr,

span: steps[i] + update_node.forward[i].span - step + 1,

};

update_node.forward[i].ptr = new_node_ptr;

update_node.forward[i].span = cur_span;

} else {

// Update the span of the pointers in update[i] above the new node, because a node was inserted.

update_node.forward[i].span += 1;

}

}

unsafe { new_node_ptr.as_mut() }.forward = forward;

self.len += 1;

None

}

Deletion is similar to insertion. A minor difference is that it returns None if the node to be deleted is not found. The overall logic is also to start from the top-left, find the update[i] for each level, and then perform the linked list deletion level by level. Note that update[i] is not the node to be deleted, but its predecessor at each level. Pseudocode:

update[i].forward[i] = update[i].forward[i].forward[i];

drop(node_to_remove); // node_to_remove is found during traversal

Search is also similar, starting from the top-left corner. We won’t go into detail here.

Since we are using raw pointers, we need to manually free the memory.

impl<K: Key, V: Value> Drop for SkipList<K, V> {

fn drop(&mut self) {

unsafe {

let mut cur = self.head.as_ref().forward[0].ptr;

while !self.is_tail(cur) {

let next = cur.as_ref().forward[0].ptr;

let _ = Box::from_raw(cur.as_ptr());

cur = next;

}

let _ = Box::from_raw(self.head.as_ptr());

let _ = Box::from_raw(self.tail.as_ptr());

}

}

}

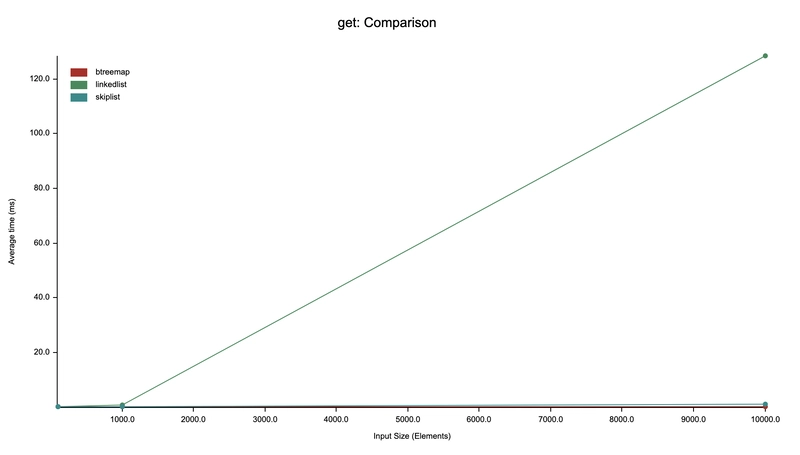

Here is a performance comparison for lookups between a Skip List, a Linked List, and a BTreeMap:

As you can see, as the number of elements increases, the performance of the linked list deteriorates sharply, while the performance of the skip list and BTreeMap remains almost constant. This again proves that the overall time complexity for lookups in a skip list is O(log N).

Both being ordered structures with O(log N) time complexity, the skip list is much simpler to implement than a Red-Black Tree. Even if you are familiar with both, the insertion, deletion, and rotation operations for a Red-Black Tree can take a full day to write, whereas a complete skip list can be written in half a day. Furthermore, the skip list’s elegant embodiment of the space-for-time trade-off makes it a very graceful data structure.