We often think we understand the systems we interact with every day. If you ride a bicycle, you know how it works. But do you?

Join the Advent of System Seeing and follow along with the prompts

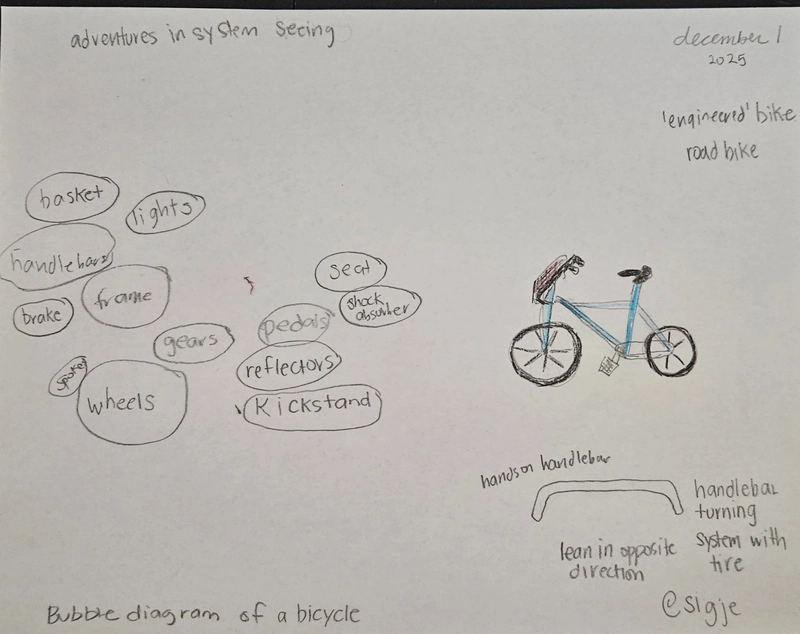

To kick off December, my family and I joined Ruth Malan’s “Advent of System Seeing.” The Day 1 prompt sounds deceptively simple: Draw a bicycle. The goal isn’t art; it is a warm-up exercise for your brain. It forces you to take your fuzzy mental models and make them concrete on paper. When we sat down to do this—covering bubble diagrams, memory sketches, and reflection—we quickly realized that “the system” looked completely different to each of us.

The first part of the prompt asks for a bubble diagram to show key concepts and relationships.

This was where my brain went immediately. My drawing was a network of functional parts, for example, frame, gears, seat, and shock absorbers. My husband, Brian, pointed out that this was a distinct “engineering mind” view. I was defining the system by its internal architecture.

However, even my “engineering” view had gaps. As I described what I was attempting to draw, for example the complex braking systems, Brian noted, “Most bikes don’t have complex brakes. Frankie’s doesn’t have calipers or cantilevers”. I was drawing my bike and it’s important to make that distinction as there isn’t just one perfect bike.

The next step is to sketch a bicycle from memory without looking at one. This is where the illusion of explanatory depth usually collapses.

Brian struggled to draw the bike in isolation. For him, the system was incomplete without its environment. He eventually drew a rider—a figure resembling Abraham Lincoln—and a cat in a basket. He realized that it was actually easier to draw the mechanics once he placed a human in the center.

This mirrors a reflection from Sebastian Hans, another participant in the challenge: “The system only works at all in connection with its environment. Without the ground, the bicycle doesn’t move.” Brian couldn’t see the system until he saw the relationship between the machine and the user.

Then there was our son, Frankie. While the prompt asks us to notice what is there, Frankie focused on what should be there.

His mental model of a “functional bike” included rocket launchers and a puppy (heavily influenced by the block style art of Minecraft). His default starting point was actually a tricycle. This sparked a real debate about the boundaries of the system—specifically, does a tricycle count when drawing a bicycle? It was a reminder that users often bring expectations to a system that the designers never anticipated.

Ruth Malan sums up the purpose of this exercise: “Our mental models are incomplete, but we don’t know this until we really engage with them.”

We assume we know how the parts connect. We assume we know what the user needs. But when we are forced to draw it out, we see the gaps.

- I saw the mechanical structure.

- Brian saw the human relationship.

- Frankie saw the potential features.

None of us were wrong, but none of us had the full picture alone. To build better systems, we have to stop assuming our mental model is the only one that matters. We have to pick up a pencil, draw, share our drawing, and then see what everyone else is drawing.

You can join the “System Seeing” practice yourself. It only takes 15-20 minutes.

- Visit the prompt: Go to Ruth Malan’s Day 1 page.

- Don’t skip the bubble diagram: It reveals how you structure relationships in your head.

- Compare notes: Share your drawing (or a link to your drawing) in the comments and let’s talk about it! The differences in the drawings are more valuable than the drawings themselves.