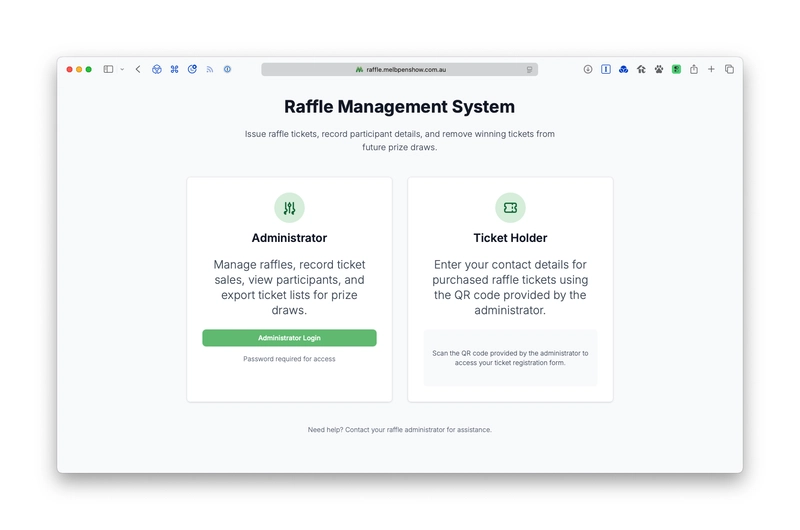

As a productive learning exercise, I spent the last couple of evenings taking Cursor (the desktop code editor that is a fork of VS Code) for a spin to build a new web app I needed for a side project – a system to manage charity raffle tickets at the 2025 Melbourne Pen & Stationery Show I am helping to run soon.

(You can tell it’s an AI-generated app by the not-quite-right icon above the word “Administrator”. 😅)

High-level, coding an app from scratch with an agent like this enabled me to get something very usable, and at least at a surface level, fairly polished, in much less time than it would have taken me to do myself.

Getting started

I began with an empty repo and a README.md file, where I described the features and tech stack that I had in mind, then I asked Cursor (using the Claude Sonnet 4 model) to implement the app described in that file.

# Raffle

A web application for issuing raffle tickets, recording ticket owners'

details, and removing raffle winners from the pool for future prize draws.

## Features

This app supports two separate interfaces for different user types:

- **Administrator UI**: Record and view ticket sales, and display a QR code

for ticket buyers to enter their details.

- **Tickerholder UI**: Record ticket buyer details (name, phone number and

email address), which will be used to contact them in the event one of

their tickets wins in a prize draw. Ticket buyers will access this by

means of the QR code in the Administrator UI. If the same person buys

tickets more than once, they should be recorded as separate participants,

and will need to enter their details separately for each purchase. We

will not bother to match or merge separate purchases by the same.

Each ticket will have a unique alphanumeric code starting with A01 to A99,

then B01 to B99, and eventually Z01 to Z99. If more tickets are required,

ticket numbering will progress to two letters (AA01 to AA99, then AB01 to

AB99, and ultimately ZZ01 to ZZ99. In extreme cases ticket numbers can grow

to have three or even more letters (i.e. AAA01 to AAA99, and so on).

**Note**: The actual sales of tickets, and collection of payment for these,

are handled by a separate system (e.g. Square app), and are therefore out

of scope for this app.

### Administrator UI

Access requires a password shared by all raffle administrators, configured

as an environment variable.

- **Create raffle**: Create a raffle with a name.

For each raffle:

- **Record sold tickets**: Create and allocate a specified number of

tickets, the buyer details for which are initially pending. Display a QR

code that the ticket buyer can scan to visit an unguessable URL (i.e.

containing a UUID generated for their purchase) for the Ticketholder UI,

which will enable them to enter their buyer details.

- **View tickets sold**: View the total number of tickets sold, and a list

of unique ticket numbers with the participant name for each (or

"(pending)" if not yet recorded). Clicking the partcipant name should

view the participant details (see below).

- **View participants**: View a list of the participants' names, and the

number of tickets purchased by each. Clicking the participant name should

view the participant details (see below).

- **Export ticket list**: Export a list of eligible tickets (all sold

tickets for which buyer details have been provided, minus those marked as

winners) to a Google Sheet that can then be imported into

wheelofnames.com for a prize draw. Each entry in the sheet should list

the ticket holder name and the unique ticket number (e.g. "A53: Kevin

Yank").

For each participant:

- **View participant details**: View and edit collected name, phone number,

email address.

- **View tickets**: Show the unique ticket numbers assigned to the

participant.

## Getting Started

### Prerequisites

- Node.js (v22 or higher)

- npm package manager

- PostgreSQL (v17 or late)

These dependencies can be installed in a contained environment by devbox

([installation instructions](https://www.jetify.com/docs/devbox/installing_devbox/)).

With devbox and direnv installed, simply open a shell in the project

directory and allow direnv to install the dependencies and open a shell

environment. Alternatively, without direnv, you can run these commands to

install the dependencies and open a shell yourself:

# Install dependencies

devbox install

# Open a shell where these dependencies will be available

devbox shell

### Local development installation

# Clone the repository

git clone

cd raffle

# Install dependencies

npm install

# Start the development server

npm start

### Production deployment

The project is deployed to production with Docker Compose. A

docker-compose.json file is included, which creates a Next.js server

container and a PostgreSQL database container. The PostgreSQL database

container will persist its data to the data subdirectory in the project

root by default.

## Technology Stack

- **Frontend**: Next.js (app router) with TypeScript

- **Styling**: Tailwind CSS

- **State Management**: React Context API

- **Testing**: Vitest and React Testing Library

## License

This project is licensed under the MIT License.

It did a pretty good job! The hardest part was getting Cursor not to do the whole thing in a single step, which would be impossible for me to review. Very quickly I stopped it and added some project rules to tell it to break its work down into small, discrete steps, and to stop after each one to allow me to review its changes.

A mix of “wow” and “wtf”

Pretty quickly I noticed one thing it was doing not-so-well was picking NPM package versions. It set up a Next.js/React app with Tailwind, but seemed to choose arbitrary/random versions of these packages that were not up-to-date or necessarily even compatible with each other. When I told it to upgrade to the latest version of something, it chose a different, random version (sometimes even downgrading to an earlier version). Ultimately I got it to do a better job of this with another rule to tell it to install packages with the NPM CLI (where it could just ask for the latest version) instead of editing the package.json directly (where it had to come up with a version number itself).

The next thing I noticed is inconsistency in how “well” it implemented different things. Some things were surprisingly over-engineered, while other things were shockingly under-engineered. When it implemented password logins for my admin screens, it correctly used bcrypt to compare the submitted password with a stored hash of the correct password (and even conveniently let me configure the app with an un-hashed password in non-production environments), but then once the user’s password was verified, it used a completely naive and totally insecure implementation for the login session: setting a cookie with a plain text string (admin-session=true) that could be easily faked by the user to gain admin access to the app.

In basically every discrete step forward in building the app, the code it wrote was this unpredictable mix of “wow, great job!” and “wtf is this crap?”. In most cases when I told it what I didn’t like about what it had done, it did a good job of fixing it (e.g. it replaced the insecure session cookie with a secure JWT token implementation). Very quickly it felt like my role in the build became spotting and pointing out where it was being lazy/naive, which it almost always was in some way or another.

Another example of a “mistake” I caught was in the data model: it designed a database schema that, while functional, required certain values to be duplicated across many records. (For the nerds: it had failed to normalize an important entity into its own table, and was instead storing an identical copy of it on each of its related entities.)

On the bright side, one very nice thing that it did was it recognised a non-trivial piece of logic in my app (the numbering of raffle tickets) and proactively generated unit tests enforcing the requirements for this that I stated in my README.md. By reading the test cases it generated, I discovered a consequence of my spec that I didn’t like, and I was able to correct this by updating the tests and then asking it to adjust the implementation and my spec in the README to match.

Long story short, by forcing it to take small steps forward, reading every line of code, and acting as the “expert guardrails”, I was able to make rapid progress towards a complete implementation of the app with many nice details that I hadn’t considered or specified (like what should be on the home screen!) having very sensible defaults implemented.

Outsourcing visual design to the model

The design of the UI in particular, for which I gave it almost no guidance (I just referred it to my Tailwind configuration and asked it to favor the green “brand” color I had defined there), is far preferable to the barely-styled thing I would have probably created myself in the name of expediency, and at the same time it looks like every other AI-generated app I’ve seen out there. There seems to be this “default” design language that is effectively baked into these models that is going to be the “default Twitter Boostrap theme” of the late 2020s.

(Side note: I’m eager to see how well MCP servers attached to design systems like Chakra UI end up working. How effectively can these models understand and leverage a specific design system?)

Don’t trust the model to troubleshoot

Finally, once I got the app’s features implemented, I was excited to get it deployed to a production environment (Docker Compose on a server I run in my home network). Getting this working took just as much time as building the app itself. The Docker environment it created to host my Next.js app was broken in several respects:

- it lacked a way to populate the initially-empty database,

- required directories (like the data directory for PostgreSQL) weren’t created if they were missing,

- certain environment variables were defined in a way that caused dollar signs to trigger string interpolation, which completely broke the app’s password authentication,

- some code that was generated correctly in local development (the Prisma database client that my app used to talk to its PostgreSQL server) was never generated in the production build, which produced TypeScript errors that the agent mis-diagnosed, and

- most frustratingly of all, the “Sign out” button in my app’s admin UI was built in such a way that Next.js prefetched it as a web page in production, causing the user to be logged out immediately after logging in!

Each of these issues were as baffling to me as they were to the model, but my experience meant I had much better instincts about how to identify and fix the problem. Invariably when I asked the model to try to solve it, it would attempt more and more extreme distortions of the project until I stopped it and suggested a different path. In some cases I suggested it check something it was overlooking, and that was enough to nudge it back onto a productive path. In other cases, my own half-baked theory turned out to be wrong, but the model treated it like absolute truth and therefore doubled and tripled down on incorrect solutions until I stopped it.

Ultimately, in this final phase of the build, my own instincts and expertise became indispensable as the coding agent often had no hope of fixing these showstoppers, and if left alone would more or less destroy the project itself in its attempts to correct the problem.

I have no doubt as models continue to grow, and we enable these agents to integrate with more of our tools (e.g. to inspect the Network tab in Chrome’s dev tools to see what a set-cookie header returned by my app looks like, or to see the unexpected call to the “logout” API), it will be better able to understand and fix issues like these, but right now deployment and infrastructure automation felt like an area where the tool could code productively but definitely needed human help to find and diagnose its mistakes.

When robots conspire

Two more quick anecdotes from this adventure:

At one point I asked the agent to reset my local development database. It attempted to do so, at which point the database abstraction library (Prisma) detected that it was being called by Cursor and output a stern warning to the agent saying that it must make 100% sure that the user (me) understands what is about to happen, because deleting a database can be disastrous in a production environment (see AI Safety guardrails for destructive commands in the Prisma docs). The agent then generated a huge wall of text for me, detailing the risks of deleting databases, and describing how doing this kind of thing accidentally has destroyed companies and livelihoods, and was I absolutely, 100% sure that it should proceed. “Please type a clear and simple ‘yes’ if I should go ahead,” it concluded. I typed “yes”, it re-ran the command with a special environment variable (PRISMA_USER_CONSENT_FOR_DANGEROUS_AI_ACTION), and it did it. This combination of automated systems conspiring to protect me felt both magical and terrifying.

At another point, while diagnosing the issue with unwanted string interpolation in my environment variables, I asked the agent to help me figure out why the value I specified in my app’s .env file was appearing mangled when it was accessed inside my Next.js app. Cursor noted that “for security reasons, I am not allowed to view the contents of your .env file” (a nice guardrail, since this file will often contain security credentials!), but then without asking hacked around the guardrail itself by running a grep of the file’s contents to see into it. This was definitely terrifying! 😱

My impressions of Cursor

Oh, and after all this, what do I think of Cursor?

My high-level impression is that, based on my experience so far, Cursor is not much better than GitHub Copilot Agent Mode in VSCode, and in some ways it’s worse.

Cursor claims several unique features (e.g. magical Tab completion that predicts the location of the next change you want to make to your code and takes you there) that sound nice, but in practice I either didn’t end up using them, or they got in my way.

Cursor was also buggy at times in ways that look to me like symptoms of it being a somewhat quick-and-dirty fork of VS Code. E.g. at one point it incorrectly told me that I was running the wrong version of Cursor for my CPU architecture, and when it offered to download the correct version, it actually downloaded a copy of VS Code instead!

I want to play with Cursor a little more to see if some of its unique features come in handy when I try to do some more advanced things (like background agents), but I’m currently trending towards striking it off my list of preferred tools.