Moving beyond static infrastructure definitions is the next major step in mastering Infrastructure as Code (IaC). While hardcoding values in a single .tf file works for a simple proof of concept, real world cloud environments demand flexibility, reusability, and consistency. This is where Terraform Variables become indispensable.

Terraform variables eliminate the need to repeat values across multiple resources and allow the same code to be easily deployed across different environments (Dev, Stage, Prod) simply by changing an input value.

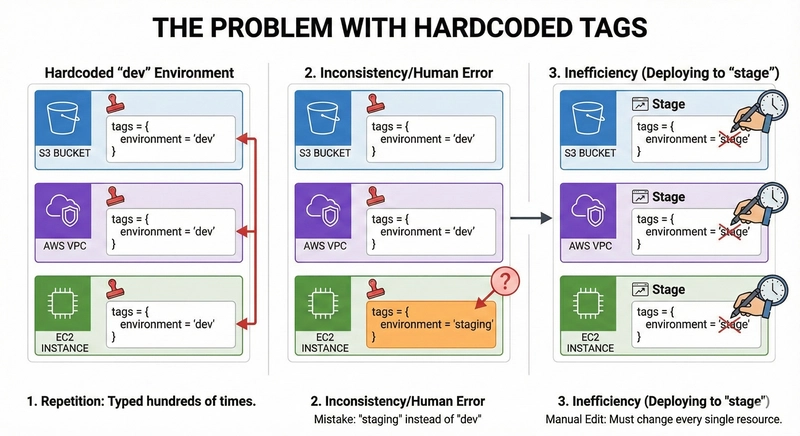

The Problem with Hardcoding

Imagine defining multiple resources such as: S3 bucket, an AWS VPC, and an EC2 instance, all intended for a “dev” environment. If you hardcode environment = dev into the tags of all three resources, you face several challenges:

1. Repetition: You type the same value hundreds of times across dozens of resources.

2. Inconsistency/Human Error: A simple mistake, such as typing “staging” instead of “dev” in one resource’s tag, makes your infrastructure inconsistent.

3. Inefficiency: To deploy the same infrastructure for a “stage” environment, you would have to manually edit the tag value in every single resource block.

Variables: The Three Types Based on Purpose

Terraform categorizes variables into three main types based on their purpose in the workflow:

1. Input Variables: These are variables defined by the user to provide values that will be used throughout the Terraform configuration. They are the most common type and include values like environment names, region names, or CIDR blocks.

2. Local Variables (Locals): These variables are used for internal computations or string concatenation within the configuration. They help create consistent naming conventions or complex tags by combining multiple input variables or resource attributes into a single reusable internal value.

3. Output Variables: These variables expose important information about the created resources to the console or other configurations (modules/scripts) after the terraform apply command runs. Examples include the generated VPC ID or the EC2 Instance ID, which are not known until the resources are created.

Code Example: Input and Local Variables

The following HCL demonstrates how to define an input variable and use a local variable for sophisticated naming:

// 1. INPUT VARIABLE Definition

variable "environment" {

default = "dev"

type = string

}

// 2. LOCAL VARIABLE Definition (for consistent naming)

locals {

// Uses string interpolation (via ${...}) and the input variable

vpc_name = "${var.environment}-VPC"

}

// 3. RESOURCE Definition using Variables

resource "aws_vpc" "sample" {

// Accessing Input Variable

cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/16"

tags = {

// Accessing Local Variable for consistency

Name = local.vpc_name

Environment = var.environment // Accessing Input Variable

}

}

// 4. OUTPUT VARIABLE Definition

output "vpc_id" {

value = aws_vpc.sample.id

}

In the example above, var.environment is the input, and local.vpc_name is an internally defined value that combines the input with a static suffix (-VPC), adhering to the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle.

Variable Precedence: How Terraform Chooses a Value

A critical aspect of using input variables is understanding the **precedence **the order in which Terraform sources and applies variable values. When a variable is declared in multiple places, the one with the highest precedence wins.

Here is the general precedence order from Lowest to Highest:

1. Default Value: Defined directly inside the variable block (e.g., default = "dev". This has the lowest precedence.

2. Environment Variables: Values defined via shell variables using the format export TF_VAR_ (e.g., export TF_VAR_environment=stage). This overrides the default value.

3. Auto-Loaded Files (.tfvars): Variables defined in files named terraform.tfvars, terraform.tfvars.json, or any file ending in .auto.tfvars. These are autoloaded and have higher precedence than environment variables.

4. Command Line (-var / -var-file): Values supplied directly when running terraform plan or terraform apply using the -var or -var-file flags (e.g., terraform plan -var="environment=prod"). This has the highest precedence and overrides all other methods.

This hierarchy allows engineers to set stable defaults while giving deployment scripts the flexibility to override those values with production-specific configuration via the command line.

Variable Types (Type Constraints)

Variables must adhere to specific type constraints (or data types):

• Primitive Types:

◦ String: Characters, letters, and words (e.g., “dev”).

◦ Number: Numeric values (e.g., 100).

◦ Bool (Boolean): Returns either true or false.

• Complex Types: List, Set, Map, Object, and Tuple.

• Special Types:

◦ Any: If no type is explicitly defined, Terraform automatically selects the type based on the provided value.

By mastering these concepts—the variable types, usage syntax (var.environment), and the critical precedence hierarchy, you can begin writing modular, consistent, and scalable Infrastructure as Code.

Video from original challenge

Below is the foundational video that dives into these concepts, explaining input, output, and local variables in detail (from “Tech Tutorials with @piyushsachdeva “)