The software industry has an addiction. We’re addicted to complexity, to chasing the scaling problems of companies we are not, and to the performative theater of “best practices” we don’t truly understand. But our most dangerous addiction is the one we refuse to talk about: we’re addicted to lying to our users.

Not big, overt lies. We tell the small, socially acceptable lies of a profession that has mistaken a fancy dashboard for an honest conversation.

It was 3 AM, and PagerDuty was screaming. A core database cluster had decided to take an unscheduled vacation. Our primary API was dutifully returning a sea of 500 errors. The on-call engineer was deep in the digital trenches, fighting the good fight.

And our status page? Our beautiful, hand-crafted status page, our supposed single source of truth, was a serene, confident, and utterly dishonest shade of green.

All Systems Operational.

As our support was flooded with the digital pitchforks of angry customers, we learned a hard, expensive lesson. A status page that isn’t automated isn’t a source of truth; it’s a liability. A billboard that seems to highlight a lack of competence.

That night, we didn’t just have a technical outage: we had a trust outage. The code was fixable. The database would recover. But the trust we torched with every customer who saw our green-lit lie while their own business was failing? That debt is difficult to repay.

Most status pages are a joke. They are marketing collateral, designed to project an image of stability that is often pure fiction. We’ve been conditioned to accept this. We see a competitor’s page showing green during a known AWS outage and we just nod along. It’s all part of the game.

This is insanity. And it’s costing you customers.

We rebuilt our entire incident communication strategy from the ground up, not as a technical exercise, but as a business imperative. Here are the seven, non-negotiable steps we took to stop lying and start building a platform our customers could actually trust.

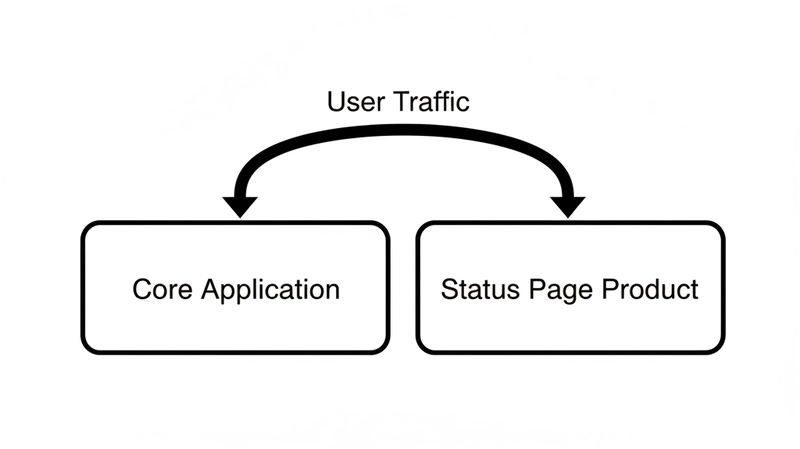

Step 1: Treat Your Status Page as a Product, Not a Panicked Afterthought

Let’s be honest about how most status pages are born. An executive sees a competitor has one, or you suffer a massive, embarrassing outage. A mandate comes down: “We need a status page!”

So a team, already overworked, is tasked with bolting one on. They grab the cheapest option, or roll out a static page and do the bare minimum integration, and check the box. It sits there, an orphaned artifact of a past crisis, waiting to be manually updated by a panicked engineer who has a thousand more important things to do.

This is fundamentally broken.

Your status page is a critical, customer-facing product. It is as much a part of your user experience as your login form or your billing settings. During an incident, it might be the only part of your product a customer can interact with. To treat it any less than professional is neglect.

A product has a purpose. It has a target audience. It has reliability requirements. It requires design thinking, engineering rigor, and ownership. When you frame it this way, the idea of having a “manual” status page becomes as absurd as having a manual signup form where a human has to create a user account in the database by hand.

Stop thinking of it as a cost center or a checkbox for your CISO. It’s a retention tool. Every dollar you invest in making your communication clear, timely, and honest during a crisis will pay for itself tenfold in reduced churn and lower support costs. Your customers don’t expect perfection, but they demand honesty. Your status page is where you deliver it.

Step 2: Your Customers Aren’t a Monolith. Stop Talking to Them as If They Were.

The second cardinal sin of incident communication is the firehose approach. A minor service feature used by 1% of your user base experiences a hiccup, so you blast a notification to everyone. You update the main status to a concerning shade of yellow, causing panic and a flood of support tickets from customers who were never, and would never be, affected. Or worse, you don’t offer any notifications.

This is lazy. I believe there is room for improvement in how we value our customers’ time and attention.

Your user base is segmented.

- Internal Teams: Your own engineers, support staff, and sales teams need a high-fidelity, unfiltered view of what’s going on. They are your front line.

- All Public Users: The general audience for your product. They need to know about widespread issues affecting core functionality.

- High-Value Enterprise Customers: These clients might be on dedicated infrastructure or use specific API endpoints. They need targeted, precise communication that is relevant only to them. Telling them about a problem with your free-tier user onboarding is just noise.

A send-to-everyone communication strategy serves no one. The solution is to have different channels for different audiences. Use public pages for public problems and private, dedicated pages for internal teams or specific enterprise clients.

This isn’t about hiding information; it’s about delivering the right information to the right people. It’s the difference between a targeted message and spam. Your customers will thank you for it.

Step 3: Decompose Your Comms, Not Just Your Codebase

The industry is obsessed with microservices. We spend years decomposing our monolithic applications into a distributed tangle of services, arguing about service meshes and YAML configuration until our eyes bleed. We do this in the name of “separation of concerns.”

Then we take this beautifully decomposed system and represent its health with a single, monolithic status: “Services: Ok”.

The hypocrisy is astounding.

If your system is made of distinct, user-relevant parts, your status communication must reflect that reality. Stop telling people the “Service” is degraded. What does that even mean? Is the login page slow? Can they not process payments? Are background jobs failing? Is the public API returning errors?

Break your status page down into granular, logical pieces that mirror the way your users actually experience your product.

- Public API

- Web Dashboard

- Payment Processing

- Third-Party Integrations (Stripe, Twilio, etc.)

- Background Job Processing

This granularity does two powerful things. First, it allows for incredibly precise communication. An outage in “Background Job Processing” is far less alarming to a user trying to log in to the dashboard than a generic “Major Outage” banner.

Second, it empowers users to help themselves. By allowing them to subscribe to updates for only the services they care about, you move from a broadcast model to a self-service model. The engineer who only cares about the Public API doesn’t need to be woken up because the Web Dashboard is having a CSS issue.

This isn’t complex. It’s just applying the same “separation of concerns” logic we champion in our code to the way we talk about that code with our customers.

Step 4: Red, Yellow, Green is a Traffic Light, Not a Communication Strategy

Let’s talk about the tyranny of the three-color system. Green: Ok. Yellow: Partial Outage. Red: Outage.

These statuses are functionally useless. They are corporate jargon masquerading as information. “Partial outage” is the single most frustrating phrase on status pages. Partially down for whom? By how much? Is it a 50ms increase in latency or is every other request timing out?

This ambiguity serves only one party: the vendor. It allows you to admit there’s a problem without providing any real, actionable information. It’s a hedge. And your customers see right through it.

We need to move beyond the traffic light and embrace descriptive statuses. These are explanatory, human-readable states that provide genuine insight into the nature of the problem.

Instead of Partial Outage, try:

- Increased Latency

- Delayed Deliveries

- Intermittent Connection Errors

- Social Auth Unavailable

Precision builds trust. Vague platitudes destroy it. Using precise, semantic language demonstrates that you have a deep understanding of your own system and that you respect your customers enough to tell them the truth, even when it’s complicated. This requires a system that allows you to define your own statuses, which is a small technical detail that has a massive impact on customer perception.

Step 5: The Only Honest Status Page Is an Automated One

This is the central thesis. Everything else is secondary. If a human being has to remember to update your status page during an incident, your status page will eventually lie.

It’s not a matter of if, but when.

When an incident hits, your on-call engineer is juggling a dozen tasks. They are analyzing logs, looking at dashboards, restarting services, and collaborating with their team in a frantic Slack channel. Their cognitive load is maxed out. Their one and only priority is to fix the problem.

The Trello card or manual checklist item for “Update the status page” is the first thing to be forgotten. It is a secondary, administrative task that demands singular focus on the technical solution.

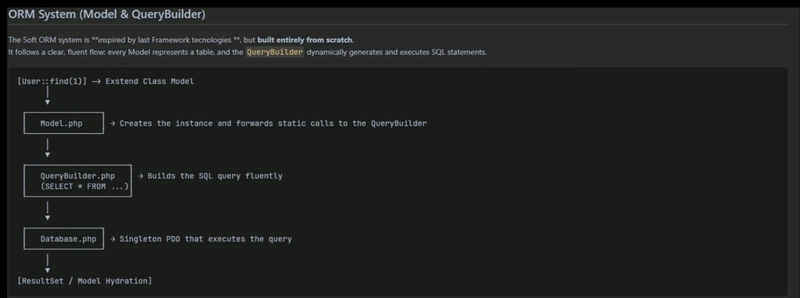

To solve this, you must remove the human-in-the-loop failure point. Your monitoring system (the thing that detected the problem in the first place) must be the same system that drives your public communication.

The goal is to eliminate the human-in-the-loop failure point and close the loop between detection and communication. This is the core philosophy behind modern platforms that integrate global checks to ensure your status page is an accurate reflection of your systems’ actual health.

When your primary monitoring tool (be it AWS CloudWatch, Datadog, or something else) detects a spike in API errors, it should automatically and instantly update the “Public API” on your status page to “Increased Error Rate” and notify subscribers.

The engineer is now freed from the burden of being a press secretary. They can focus exclusively on the fix, confident that the communication is being handled correctly. This isn’t a nice-to-have; it is the only way to guarantee an honest and timely flow of information when it matters most. Anything else is just security theater.

Step 6: Maintenance is Communication. Schedule It Like You Mean It.

Incident communication isn’t just for things that break unexpectedly. Some of the biggest trust-destroying moments happen during planned maintenance. You send one cryptic email a week in advance, then bring the system down at 2 AM on a Tuesday, only to discover that’s a critical time for your customers in a different time zone.

Proactive communication is a sign of a mature, professionally run engineering organization.

Your process should be as rigorous for planned maintenance as it is for an unplanned outage:

- Schedule in Advance: Give customers ample warning, not just hours.

- Allow Subscriptions: Let users subscribe to notifications specifically for scheduled maintenance.

- Use Clear Language: Don’t just say “System Maintenance.” Explain the scope (“Database Upgrade”), the expected impact (“Dashboard will be read-only”), and the precise window.

- Provide Updates: Just like a real incident, post updates when the maintenance begins, if it’s extended, and when it’s complete.

Treating maintenance with this level of seriousness shows respect for your customers’ businesses. It allows them to plan around your downtime, reduces their anxiety, and reinforces the idea that you are a reliable partner, not just a chaotic vendor.

Step 7: Your Post-Mortem is Incomplete if You Ignore the Communication

After the fire is out, every good SRE team conducts a blameless post-mortem. We dissect the technical root cause, the timeline of events, and the actions taken. We create action items to prevent the same class of failure from happening again.

But how often do we apply that same rigor to the communication around the incident? Almost never.

A communication failure can cause more customer churn and burn more goodwill than the technical failure itself. Your post-mortem process must be extended to include a brutal and honest assessment of your communication performance.

Ask these questions after every single incident:

- Timeliness: How long did it take from first detection to first public communication? What was the lag? Why?

- Clarity: Were our updates clear and precise? Or were they full of vague jargon? (Review the actual text!)

- Audience: Did we notify the right people? Did we create unnecessary noise for unaffected customers?

- Accuracy: Did our status page accurately reflect the state of the system throughout the incident lifecycle? If not, where did the process break down?

- Tooling: Did our tools help or hinder our communication process?

The output of this analysis should be just as concrete as your technical action items. “Update runbook to clarify descriptive status usage” or “Automate service status change” are the kinds of tangible improvements that will strengthen your communication product over time.

Conclusion: From a Source of Lies to a Source of Trust

Building a trustworthy communication platform isn’t about having a prettier dashboard. It’s a reflection of your engineering culture. It’s a fundamental commitment to automated honesty over manual theater.

By treating your status page as a product, defining your audiences, decomposing your services, using precise language, automating your source of truth, planning your maintenance, and running post-mortems on your comms, you can turn your next inevitable outage into an opportunity to build, not break, customer trust.

Stop making excuses. Stop accepting the status quo. Stop lying to your customers.

What’s the biggest incident communication mistake you’ve ever seen in the wild? Share your war stories in the comments below.